Introduction

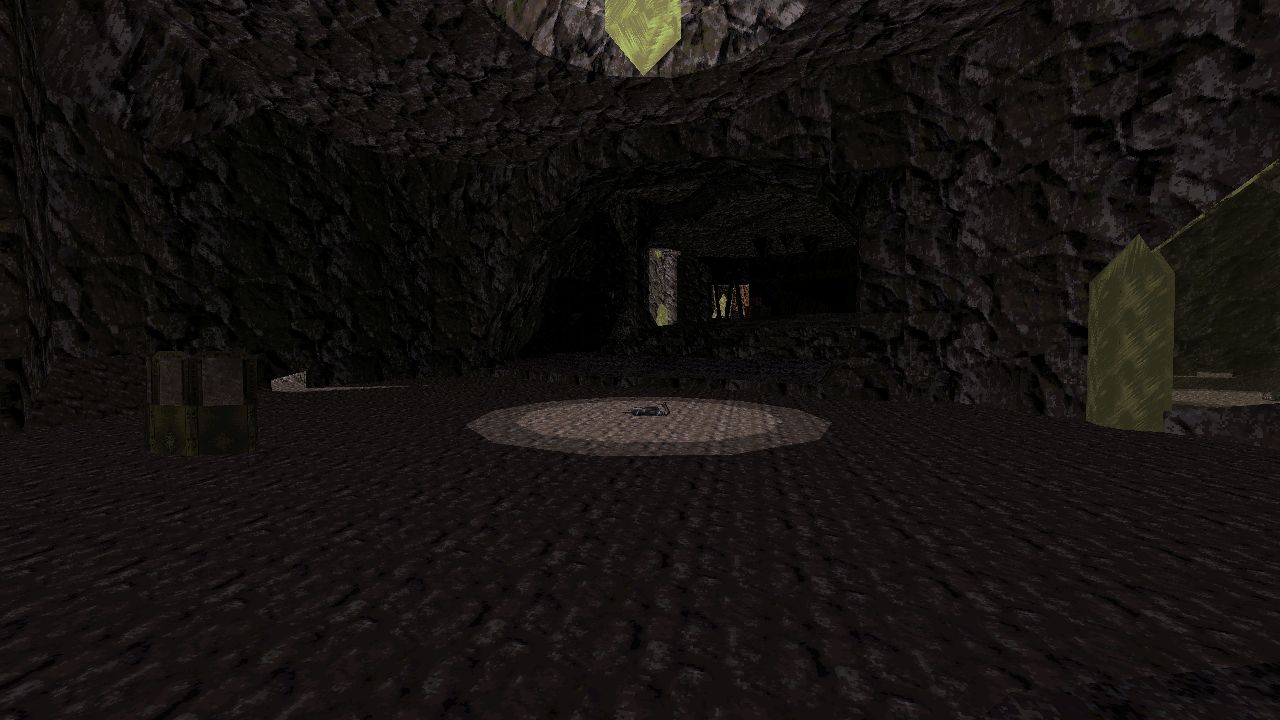

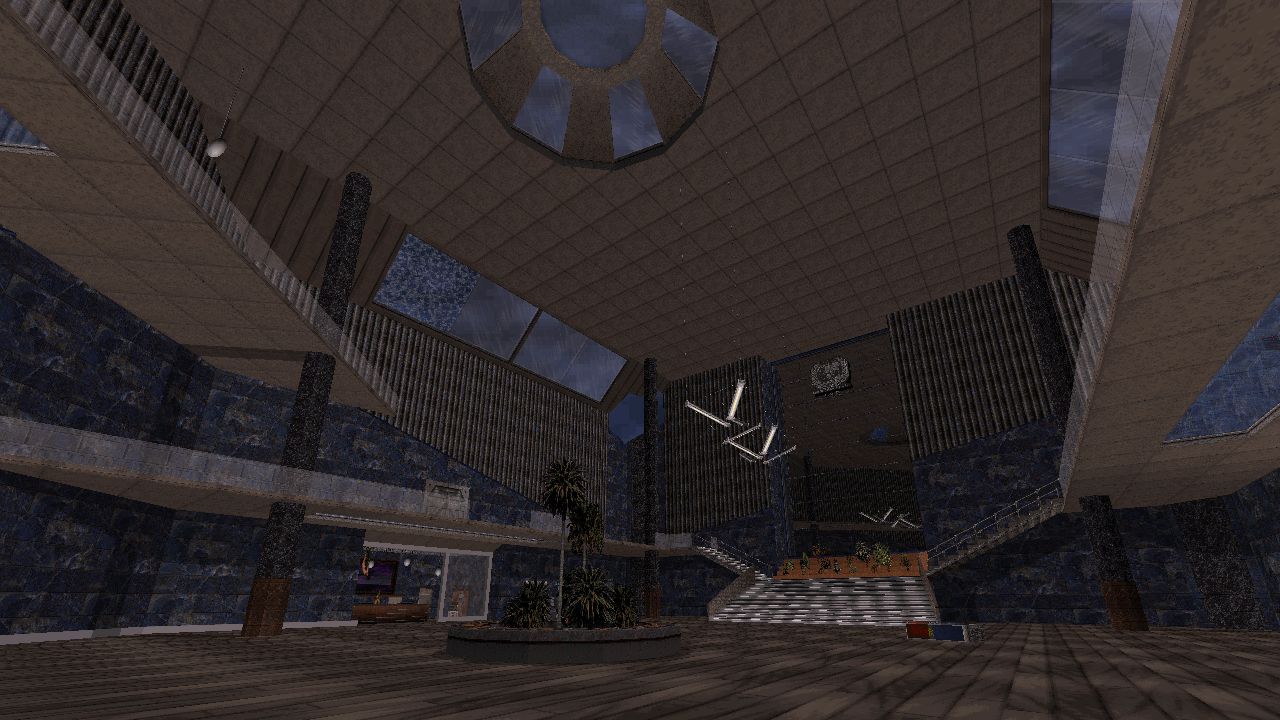

Duke has been invited to the EDF Research & Development, a laboratory focused on mining and examining green Terratin crystals serving as ammunition for an alien tech weapon, the Shrinker. Just before descending deeper underground to the main labs, an explosion sends a raging fire into the room behind him as familiar roars invade the halls. Duke must continue underground to find an alternate exit, all while cleaning house and solving a few problems along the way.

Review

Levels that lean toward puzzle solving with a focus on exploration are quick to catch my attention, especially if observing the environment is encouraged to discover clues and help with navigating around. Submachine trusts players to dive blindly into the research base to figure out problems along the way, only offering occasional guidance where necessary for its atypical gameplay scenarios. Exploration becomes a puzzle upon itself which involves the usual switch hunts and keycards, to gathering crucial information such as seeking out door codes or machine components. There are many locked doors along the main routes which may remain closed for long periods of time and card locks using the same coloured keys open separate sections from each other forcing players to pick between them before another is acquired. As progress is made the level opens up and becomes a non-linear affair providing options if stuck at any particular section. There’s always something pending that could be tackled at any given point, as all tasks found will eventually require completion to exit the facility. It all simply boils down to finding those missing elements yet to be examined.

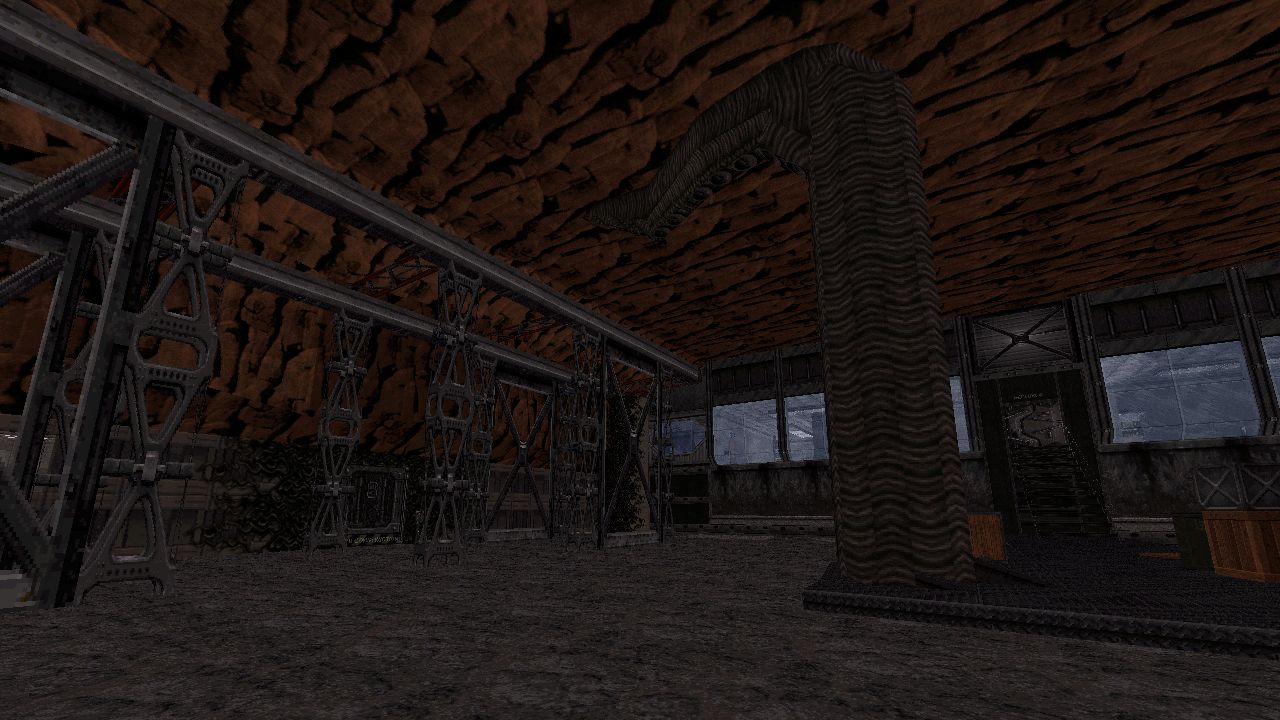

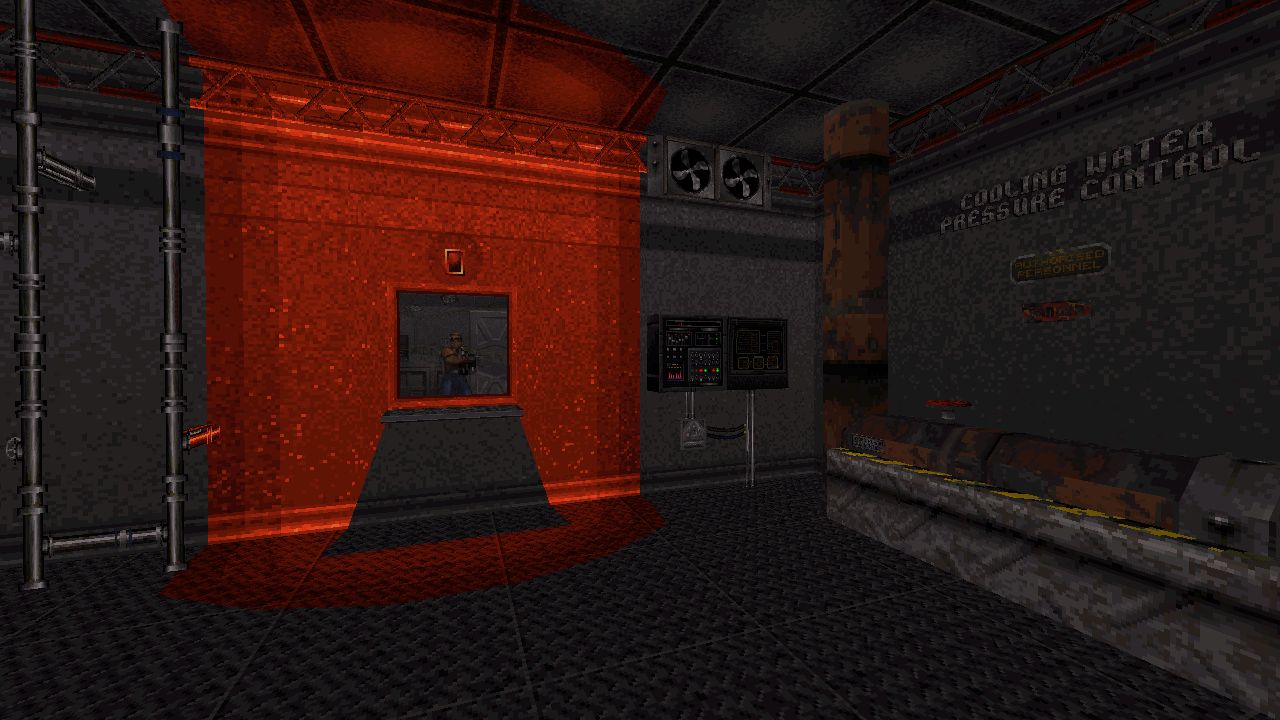

Submachine doubles as a showcase piece revealing Pistol’s deeper understanding of not only the games assets, but also its technical effects, becoming a core part of that enhances whole experience. It reminds me a little of releases like the classic BobSP series or newer works like Last Pissed Time, It Lives and Naked Dash. Levels at their time which were chock full of these unique effects, textures schemes and sprite constructions that don’t simply exist in isolation but to supplement and provide context to the current scenarios taking place. There’s all sorts of these scattered around Submachine for presentation from simple things like a light falling down on approach or a large tentacle busting out the ground and wriggling around. Others are used to gate off areas such as a laboratory leaking toxic gas that needs to be shut off or even a vehicle blocking an entryway that can be moved out of the way, complete with an entire interior design. It’s always fun seeing another take on familiar techniques available in the editor, given a fresh take to elevate a particular scene or moment. Upon entering into the second half of the underground base and seeing a cart track curving upwards with a trolley sitting there, built using a mix of regular and sloped sprites, I was wowed before having activated the sequence knowing what was to come. The concept by itself is nothing too crazy but the execution alone involves some old and new Build trickery all put to good use, laughing to myself enjoying the ride as it seamlessly climbs the ascent as the tunnels cave in from behind.

Out of sight there is even an extra side quest that involves gathering up machine parts to build a special weapon that make the finale a little easier to manage. The room to construct it must be found first before pieces can be acquired, which have been are scattered around various sections of the level and tucked away in corners to encourage going out the way to scourer each room thoroughly. It’s similar to Spacetronic’s main objective, yet the biggest key difference here was that I wouldn’t accidentally grab certain parts and not know about it. There’s a convenient list where the quest starts indicating which ones are still outstanding, including visuals on their distinct appearances that help identify them amongst the decorative elements, so I wouldn’t spend time searching for something I’d already found. Outside of exploration and navigational challenges which are simple to execute after finding a solution, there’s only a single puzzle section where the opposite is true. This involves a red keycard locked within a conveyor belt contraption. Situated on the glass is a dedicated panel for movement, expecting careful manipulation to redirect the belts and stop motion before the key drops off the edge. Failure results in the key returning to its initial starting position. Not as frustrating as I feared when first approaching it but difficult to perceive it’s relative position properly to gauge the correct time to stop going one direction and move in another, only to find the key isn’t quite lining up as thought. Having it drop into the pool can be tedious but saving can relieve that tension while foregoing the challenge to achieve it in one shot.

These two gameplay components felt the need to have fourth wall breaking explanations via monitors as to how they’re supposed to work. Not a deal breaker entirely but I do prefer approaching an in-world method to guide players through environmental storytelling or visual cues. The conveyor belt in particular could easily be learnt via trial and error with some basic instructions like an operation manual. Finding the components and building the machine could have involved more explanation from a scientist either as computer logs or a survivor having a conversation with Duke. Yet ironically one secret requires foreknowledge of an unused game mechanic without explanation whether it even exists and if it’s been applied somewhere in the level. Players may more likely attempt obvious solutions like finding a hidden switch, crawlspace or crack in the wall to gain access before moving in defeat. I’ve known that tagged door textures can be kicked to activate a trigger, but it’s never apparent when this is utilised in custom levels. Obscure mechanics are fine to play around with as this could be taught to the player through scenarios to keep the idea floating around in their mind that it’s a possibility. Perhaps kicking something is forced onto the player early to grasp the mechanic before they can proceed and is then required to progress in a few other places, while curious players will use the concept where it’s not immediately obvious but might make sense and be rewarded when it does works.

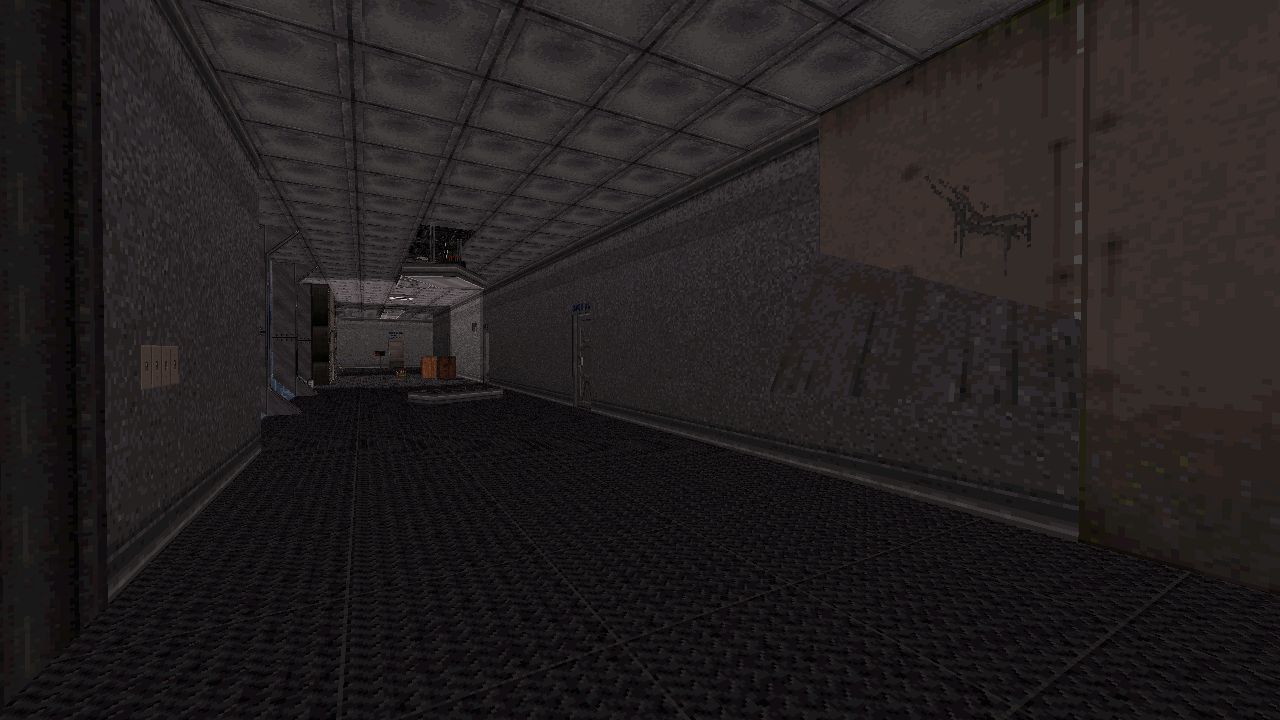

Travelling between the two separate portions of the facility did become a nuisance at times if I wanted to check on something. Navigation could have benefited from unlocking at least one main pathway by the midway point that logically links these two sections together after having explored both sides at least once. By having more free form traversal, its possible to access some areas before others causing widely different experiences while travelling the level layout. There was a shortcut in particular I found much later during my run which had lead back into the second half of the base when it no longer served any purpose by that point and could have been useful had I discovered it sooner by choosing a different red lock. Additional signage along corridor walls with directional indicators could further orientate players within the layout, similar to the earliest sections of Black Mesa from Half Life, which used colour coded lines travelling toward their marked areas. These extras could have broken up the emptier hallway designs in a meaningful way. Beside signage, another problem comes from a lack of distinctive landmarking for entryways into important areas. I don’t take issue with the interior spaces of rooms which do define themselves well, simply their placement when trying to recall where that one red or yellow card reader was again. The “Air Conditioning Control C2” door is of particular note sitting within a mundane monotone hallway, itself behind an unmarked doorway that doesn’t call attention to itself similar to a nearby closet. Less reliance on small corridors separating these vital areas and opting to open up these spaces could serve as a constant reminder for players in the vicinity. In contrast when returning to the three lab room, I’d always associate it as that bright hall with a reflective floor, always visible from the starting cavern once its door is opened as light pours into the darkness.

It got frustrating at times thinking I’m missing something while wandering around aimlessly, like holding onto a blue keycard I cannot use yet or searching for a supposed laptop with codes on it for a door I haven’t unlocked yet. The laptop in question blends far too well where I eventually found it, a primarily grey textured room with dim lighting, only appearing after receiving a distress signal. I never associated this unassuming room to be Lab A3 having not seen the signage and I’d traversed through here multiple times already, associating it as an empty space. Either a repeating sound, new light source or even a monitor camera from the laptops perspective would have helped here immensely. There are also some potential softlocks and other minor annoyances that can occur to be aware of, such as accidentally stepping off the curving trolley ride or clipping through the yellow card elevator rooftop forcing a reload or noclip cheat. There’s a small possibility players won’t grab the red key by accident before navigating back toward the starting area, therefore making it impossible to return here because the way is entirely blocked off. While only a minor nuisance and not game breaking, one of the blue keys found inside a descending lift has long enough of a delay for players to walk away and not notice the results, as if it assumes they have reason to stick around this particular spot and then wander off elsewhere wasting a bit of time.

Despite being a heavy on navigational puzzles there is an abundance of combat which consistently provides reinforcements and additional supplies as progress is made. While there is a notable lack of the hitscan enemies for a change, besides several Battlelords, there are many projectile variants in their place that can cause a little havoc amongst themselves. Commanders being tricked into blowing up fellow Octabrains or Protector Drones shrinking a few allies as collateral. Combat is otherwise by the numbers that doesn’t stand out too much beside giving players something to shoot at with the odd larger skirmishes to fill out bigger sections. There were a few standout set pieces like the Protector Drone hive waking up one by one or the Terratin Crystal cavern ambush after grabbing the yellow keycard. If fighting isn’t a preference, Piece of Cake has been tailored for players who just want to explore, solve puzzles and eat their cake in peace; There are no monsters included which almost makes sense for this style of map, except it leaves the larger sections feeling empty and lonesome. Something in-between might have been a fine balance using muted and more meaningful situational encounters, perhaps even making the Shrinker a primary weapon of choice considering the importance surrounding it. At least on paper that wouldn’t allow combat to have too much presence over other aspects. Didn’t mind the finale but not attached to it either, I’m just not keen on maps that feel it’s necessary to end on a climatic boss arena to feel like a complete package. Gorgeous interior design though.

Conclusion

As much as I enjoyed the overall experience of exploring, learning and taking in the sights, Submachine can be a little rough around the edges. There’s still a lot of charm from it’s technical effects, visual design and moment to moment gameplay as navigating isn’t so much of a problem from the initial onset venturing through the research base. Once I begin hitting a wall however and wanted to look around prior areas it becomes a nuisance backtracking and getting around comfortably to relocate specific sections. Besides some good set pieces dotted about, combat tends to feels disjointed here and gets in the way of the core gameplay style, while having no enemies on Piece of Cake doesn’t quite solve those issues either.